First Principles of Instruction and English Language Examinations: Towards a Universal Approach to Language Education?

This exploratory work reviews the first principles of instruction and employs the theory as a means of analyzing the English language examinations administered by Trinity College London and Cambridge Assessment English. Such an analysis reveals the presence of first principles, or universal principles that underlie all effective instructional design theories, in each institution’s exam designs and, by extension, their respective instructional approaches. Concluding remarks present a discussion of these early findings and consider possible avenues for further research towards a more universal approach to language education through first principles.

Key words: Cambridge, ESL, first principles of instruction, language examinations, Trinity

Introduction

The aim of this essay is to continue applying Merrill’s (2002) first principles of instruction to the field of English as a second language (ESL) education by using them as a means of instructional approach analysis. Today, Trinity College London and Cambridge Assessment English are two of the most internationally recognized ESL institutions, providing English language instruction and level qualifications around the world. Although both institutions have been very successful in the field of ESL, their respective instructional approaches differ significantly. These differences, in turn, are reflected in the formats and contents of their respective level placement examinations. In an effort to uncover these differences more clearly, this essay treats the Trinity Integrated Skills in English (ISE) II and the Cambridge First Certificate in English (FCE) exams as mirrors that reflect their corresponding institutions’ instructional approaches. Both exams are ranked as B2, or upper-intermediate, level on the Common European Reference for Languages (CEFR) scale and so represent a crucial point on the ESL learner’s path to proficiency, as the advancement from the B1 to the B2 level is considered the most challenging step by many students and teachers alike.

What follows first is an introduction to Merrill’s theory and conceptual framework. The essay then continues to apply his first principles of instruction as a means of analyzing the Trinity and Cambridge instructional approaches through the lens of their respective B2-level exams. Finally, results of the analysis are discussed and suggestions for future research towards a more universal approach to ESL instruction are provided.

First principles of instruction and motivation

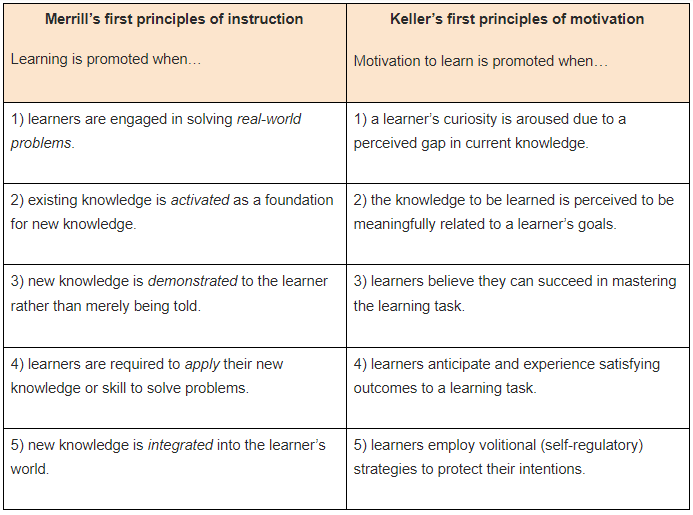

The first principles of instruction were pioneered by Merrill in an effort to uncover the universal principles that underlie all effective instructional design theories. According to his conceptual framework, a “ principle (basic method) is a relationship that is always true under appropriate conditions regardless of program of practice (variable method). A practice is a specific instructional activity. A program is an approach consisting of a set of prescribed practices” (p. 43). Therefore, the first principles identified by Merrill—task/problem-centered, activation, demonstration, application, and integration—affect all levels of learning from the bottom up, from the individual lesson plan or practice to the whole instructional approach or program. As Merrill’s theory is largely instructor-oriented, Keller (2008) further developed his first principles from the learner’s perspective, an effort that resulted in the first principles of motivation. Both sets of first principles are fully listed in Figure 1.

Ever since Merrill introduced his first principles of instruction, they have been applied broadly in numerous educational institutions as well as across various academic and vocational fields. One quantitative study of 464 students in 12 courses at an American university found that “when students agreed that their instructors used First Principles of Instruction […] they were about 5 times more likely to achieve high levels of mastery of course objectives and 26 times less likely to achieve low levels of mastery” (Frick et al., 2010, p. 2). Moreover, a qualitative study of five university professors’ experiences with the first principles of instruction revealed their successful application to the fields of family, consumer, and human development; marketing; nutrition and food science; as well as economics (Gardner, 2011). Though not extensively, Merrill’s theory has also been applied to ESL instruction. For example, Gunawardena (2019) demonstrated how first principles can be applied by teachers “to help students to develop routines of critical thinking in reading” (p. 44).

Trinity Integrated Skills in English II

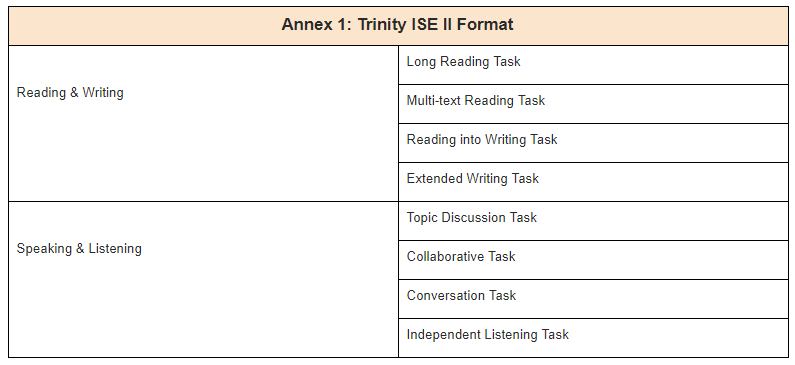

Created to test the four basic linguistic skills in an integrated and fused way, the ISE exam promotes this concept by placing the candidate in simulated real-life situations that involve interactions with other English speakers. Every ISE exam consists of two modules: Reading & Writing, on the one hand, and Speaking & Listening on the other. While these modules are generally consistent across all ISE exams, their individual tasks are scaffolded according to the level.

The Reading & Writing module of the ISE II exam begins with two reading tasks, one long reading task and a multi-text reading task . These readings, in turn, are followed by two writing tasks: a reading into writing task in which the prompt is based on the information found in the previous multi-text reading and an extended writing task that is less guided and, therefore, more free and creative in nature. The subsequent Speaking & Listening module is divided into four tasks: (1) a topic task in which the candidate must present a topic of his or her interest from scratch, (2) a collaborative task in which the candidate must elicit information from the examiner in response to an issue presented in the prompt, (3) a conversation task in which the candidate must maintain a conversation in response to the examiner’s questions, and (4) an independent listening task in which the candidate must answer a question about an audio recording. For an outline of the Trinity ISE II format, refer to Annex 1. What follows is an analysis of how the Trinity exam format integrates Merrill’s first principles of instruction:

- Learners are engaged in solving real-world problems. Although, as Merril points out, the term “problem” is understood differently among theorists, the task must be “representative [of what] the learner will encounter in the world” (p. 45). In this sense, the multi-text reading task promotes this principle. The candidate is given four texts of different nature (i.e. article, text message, statistical infographic, etc.). The task, therefore, encourages the candidates to find and connect information. Such a situation could easily occur when an English learner is at the museum or studying abroad, where information is presented in many diverse forms. On the other hand, the collaborative task in the Speaking & Listening module incorporates this principle as well. Here, the candidate is read an issue from a prompt to which he or she has to elicit further information in order to offer a final suggestion or recommendation. Thus, the task recreates a situation in which the English learner is asked for advice or needs to resolve a verbal problem that may occur in daily life.

- Existing knowledge is activated as a foundation for new knowledge. Merril explains that by this principle, “learners are directed to recall, relate, describe or apply knowledge from [...] past experiences that can be used as a foundation for the new knowledge” (p. 46). The reading into writing task upholds this principle because it requires the candidate to elaborate a written response to a prompt based on information that was previously introduced in the reading module. This triggers an activation in which the candidate has to recycle past experiences from the reading in order to produce a written response.

- New knowledge is demonstrated to the learner rather than merely being told. There is no task in the exam in which the “demonstration phase” is displayed, used, or otherwise promoted. Therefore, this principle is not adequately incorporated into the Trinity exam format.

- Learners are required to apply their new knowledge or skill to solve problems. This principle is again present in the collaborative task . Here, the candidate must apply all of his or her knowledge and linguistic skills in order to successfully organize and convey his or her thoughts and feelings with respect to the topic presented. Hence, the learner is “required to solve a sequence of varied problems” (p. 49).

- New knowledge is integrated into the learner’s world. In Merril’s words, by this principle “learners are given an opportunity to publicly demonstrate their new knowledge or skill” (p. 50). This can again be found in the collaborative task , as the candidate has the chance to show, publicly, the naturalized skill of production. Moreover, the independent listening task also integrates this principle, since the candidate has to show and, therefore, publicly prove his or her ability not only to understand but also to discern the information that is required to successfully engage in the communicative process.

Of the 8 parts that comprise the Trinity ISE II exam, 4 parts incorporate Merrill’s first principles of instruction to some degree. Of these principles, all but one (principle 3) are represented in the exam. Since the instructional approach that corresponds to the exam is reflected in the exam design, it can be said that the Trinity approach to instruction reasonably “develops authentic communicative and transferable skills that are required for academic study and employability [...]”, bringing it closer to real-life situations (Trinity College London, 2020).

Cambridge First Certificate in English

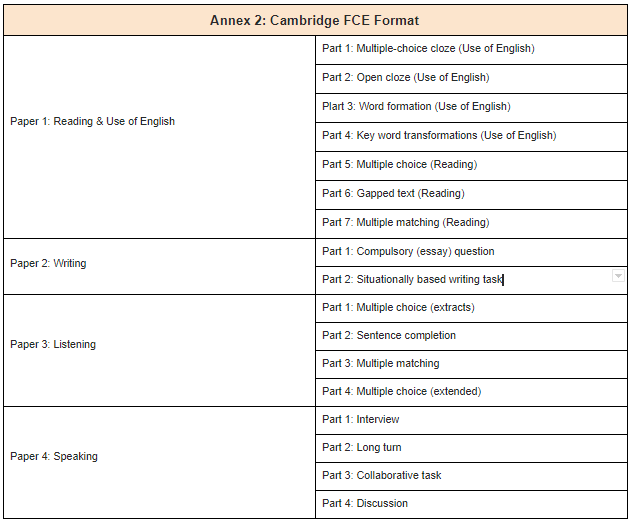

Unlike its Trinity counterpart, the Cambridge FCE exam is divided into four independent modules, called papers: Reading & Use of English, Writing, Listening, and Speaking. Besides the fact that each paper is presented separately, what is also noticeable is the inclusion of Use of English, which focuses specifically on grammar and vocabulary. This exam format is generally consistent in all intermediate and advanced Cambridge exams, with individual parts scaffolded appropriately for each level.

First, the Reading & Use of English paper has a total of eight parts: (1) a

multiple-choice cloze in which the candidate must complete a text with the appropriate words, (2) an

open cloze in which the candidate must add missing words to a text without any options available, (3) a

word formation in which the candidate must complete sentences by appropriately modifying selected root words (i.e. noun to adverb), (4)

key word transformations in which the candidate must rewrite an original sentence in an alternate form (i.e. active to passive voice), (5) a

multiple choice reading in which the candidate must answer a series of comprehension questions about a text, (6) a

gapped text reading in which the candidate must appropriately insert several sentences that have been removed from a text, and (7) a

multiple matching reading in which the candidate is provided a series of statements and must identify which part of the text contains the corresponding information.

Next, the Writing paper is divided into a compulsory essay on a given prompt and a

situationally based writing in which the candidate can choose to write either an article, an email/letter, a report, or a review. Then, the Listening paper consists of four parts: (1) a

multiple choice in which the candidate must answer questions about a series of short monologues, (2) a

sentence completion in which the candidate must complete statements about the listening with the appropriate missing words, (3) a

multiple matching in which the candidate must connect a series of different speakers with their respective utterances, and (4) another

multiple choice about an extended dialogue.

Finally, the Speaking paper also contains four parts: (1) an

interview in which each candidate is asked to introduce him or herself, (2) a

long turn in which each candidate must describe and and compare different images, (3) a

collaborative task in which two or three candidates must reach a decision about an issue proposed by the examiner, and (4) a

free discussion about the issues raised in the previous part. For an outline of the Cambridge FCE format, refer to Annex 2. What follows is an analysis of how the Cambridge exam format integrates Merrill’s first principles of instruction:

- Learners are engaged in solving real-world problems. The collaborative task from the Speaking paper incorporates this principle by requiring students to reach a mutual decision regarding a prompt provided by the examiner. For example, the examiner might ask which development would be most effective in attracting tourists to the city before providing a list of five possible initiatives. By exchanging opinions, speculating together, and comparing pros and cons, the candidates effectively recreate a professional setting in which a decision on a multi-faceted topic must be reached through verbal communication.

- Existing knowledge is activated as a foundation for new knowledge. The discussion that follows the collaborative task gives the candidates an opportunity to further elaborate and justify their opinions to the examiner. Although this section is loosely guided by questions posed by the examiner, the aim of the discussion is for candidates to express the full extent of their speaking skills and vocabulary based on the activation that took place in the preceding task.

- New knowledge is demonstrated to the learner rather than merely being told. Merrill explains that this principle includes “demonstrations for procedures” as well “visualizations for processes” (p. 47). Such procedures and processes are the focus of the word formation part of the Reading & Use of English paper. In this part, the candidate would have to complete the following example sentence with an appropriate form of the root word “nourish”: “The old dog showed signs of neglect and _____.” The correct answer to this question would be “malnourishment”, which the candidate is expected to produce by following a process that consists of identifying the necessary part of speech (noun), choosing the appropriate noun suffix (-ment), deciding whether the noun should be positive or negative (negative), and choosing the appropriate negative prefix (-mal). In order for learners to be able to distinguish different parts of speech or positive and negative words, this process must be demonstrated repeatedly through numerous examples rather than just being told. Likewise, the candidate’s ability to complete this part of the exam depends on his or her capacity to demonstrate the process of word formation independently.

- Learners are required to apply their new knowledge or skill to solve problems. This principle is present in the collaborative task of the Speaking paper, as it requires students to apply their verbal communication skills and prior knowledge of the pertinent vocabulary to solve a problem posed by the examiner.

- New knowledge is integrated into the learner’s world. Apart from the collaborative task , which requires the candidates to integrate previously acquired knowledge into the world of negotiation and decision-making, the interview part of the Speaking paper also reflects this principle. Here, candidates must present themselves to the examiner by answering personal questions with a level of formality that would be appropriate in a professional environment, thus integrating their knowledge into a real-world setting.

Of the 17 parts that comprise the Cambridge FCE exam, 4 parts incorporate Merrill’s first principles of instruction to some degree and all 5 principles are somehow represented in the exam. Since the instructional approach that corresponds to the exam is reflected in the exam design, it can be said that while the Cambridge approach to speaking does embrace several of the first principles, its approach to other language skills nevertheless fails to do so.

Discussion and conclusions

While Trinity incorporates the first principles of instruction into 4 of its 8 exam tasks, Cambridge does so in 4 of its 17 parts. Although all 5 principles can be found in the Cambridge exam format and only 4 can be found in Trinity, the first principles of instruction are significantly more present in the latter in proportion to the exam as a whole (50 percent of the tasks). As a result, the tasks in the Trinity exam format are much more integrated with one another and practical in their efforts to recreate real-world situations, while the Cambridge parts are generally separate with a heavy focus on theoretical aspects like grammar. In both exams, the Speaking module/paper—and the collaborative task in particular—incorporates the first principles of instruction most prominently.

In both exams, the collaborative tasks incorporate principles 1, 4, and 5 of Merrill’s theory. Although both tasks engage learners in solving real-world problems (principle 1), Trinity candidates face the task individually in a free exchange of ideas with the examiner, while Cambridge candidates undertake the task in pairs or groups of three within the structure of a prompt that the examiner presents to them. Although it cannot be stated conclusively, the less-structured and independent nature of the Trinity task could have a more positive impact on preparing learners for real-world communicative situations with native speakers than its Cambridge counterpart. With respect to the other two principles, which share a number of overlapping characteristics, both Trinity and Cambridge candidates must apply their new knowledge (principle 4) as well as publicly demonstrate and integrate their communicative skills (principle 5), regardless of whether they do the task independently or in groups.

In short, based on the two exam analyses, the Cambridge instructional approach incorporates more of the first principles of instruction than its Trinity counterpart. Yet, the first principles are more prevalent in the Trinity instructional approach as a whole. It should nevertheless be kept in mind that this study has been largely exploratory and should therefore be read as a first step on the path towards a more universal ESL instructional approach based on first principles. It is beyond the scope of this work to search for ways to incorporate more first principles into ESL instructional approaches. Further research should focus on doing this as well as integrating Keller’s first principles of motivation to make the learner’s perspective more represented in ESL instructional approaches. Moreover, other existing English exam models such as Aptis and TOEFL could be considered as future case studies. Although being less internationally popular than the two models proposed here, by applying Merril’s theory, they could open this exploratory study to a broader scope.

Bibliography

Frick, T. W., Chadha, R., Watson, C., & Zlatkovska, E. (2010). New Measures for Course Evaluation in Higher Education and their Relationships with Student Learning. Annual Conference of the American Educational Research Association, 1–12.

Gardner, J. L. (2011). How Award-winning Professors in Higher Education Use Merrill’s First Principles of Instruction. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 8(5), 3–16.

Gunawardena, M. (2019). Pedagogies for Scaffolding Thinking in ESL. In L. Li (Ed.), Thinking Skills and Creativity in Second Language Education: Case Studies from International Perspectives (1st ed., pp. 42–57). Routledge.

Keller, J. M. (2008). First Principles of Motivation to Learn and e3-Learning. Distance Education, 29(2), 175–185.

Merrill, D. M. (2002). First Principles of Instruction. Educational Technology Research and Development, 50(3), 43–59.

Trinity College London. (2020). ISE - Integrated Skills in English Exams.

https://www.trinitycollege.com/qualifications/english-language/ISE

Annexes

Apply first principles thinking yourself?

Would you like to apply first principles thinking yourself and have your problem-solving experience published in the First Principles Thinking Review? Then be sure to check out the submission guidelines and send us your rough idea or topic proposal. Our editorial team would be happy to work with you to turn that idea into an article.

Share this page

Disclaimer : The views, thoughts and opinions expressed in submissions published by FIPS reflect those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views held by FIPS, the FIPS team or the authors' employer.

Copyrights : You are more than welcome to share this article. If you want to use this material, for example when writing an article of your own, keep in mind that we use cc license BY-NC-SA. Learn more about the cc license here .

What's new?