From First Principles to Theories: Revisiting the Scientific Method Through Abductive, Deductive, and Inductive Reasoning

Photo by www.esri.com

The aim of this article is to examine how first principles are developed into general theories by reviewing the roles that abduction, deduction, and induction play in the three primary steps of the scientific method: hypothesis generation, hypothesis testing, and theory generation. Kant’s democratic peace theory is first used to illustrate this process, and the example is subsequently extended to show the secondary level of scrutiny that theories must undergo before they can be applied to the empirical world. The article concludes by considering the strengths and weaknesses of scientific theories, particularly in the field of social sciences.

Keywords: first principles, theories, abduction, deduction, induction

Introduction

While the modern scientific method is often attributed to the revolution in human reason and rationality that swept across Europe in the age of Enlightenment, its individual steps had actually undergone one thousand years of development and refinement before they were finally assembled into a systematic process of inquiry by scholars between the 17th and 19th centuries. It was Aristotle who first distinguished between deductive reasoning, a top-down form of logic whereby conclusions are inferred from empirical observations and fundamental rules, and inductive reasoning, a bottom-up form of logic by which fundamental rules are extrapolated from conclusions based on empirical observations.

In the pursuit of solutions to real-world problems, both methods have been complementary to one another in that deduction allows the researcher to use fundamental rules, or first principles (as Aristotle refers to them), to reach specific conclusions that can later be used to produce generally applicable theories through induction. By repeating this endless process of rigorous scrutiny with the observable yet unexplained phenomena of the natural world, philosophers have been able to create an epistemological framework for human understanding that encompasses everything from Darwin’s theory of evolution in the natural sciences to Marx’s theory of revolution in the social sciences.

Deduction, induction, and first principles

Rene Descartes, a renowned advocate of deductive reasoning, explored the relationship between deduction and first principles. In his

Principles of Philosophy, Descartes explains that first principles must possess two conditions. First, “they must be so clear and evident that the human mind […] cannot doubt of their truth” and second, “the knowledge of other things must be so dependent on them [that although] the principles themselves may indeed be known apart from what depends on them, the latter cannot […] be known apart from the former” (Lancaster University, 2003). Accordingly, it is necessary to deduce from those first principles the knowledge of that which depends on them, as “there may be nothing in the whole series of deductions which is not perfectly manifest” (Lancaster University, 2003).

Francis Bacon, a contemporary of Descartes, makes a similar observation. Referring to first principles as axioms, he notes that if a general axiom proves false, then all intermediate axioms deduced from it may be false as well. For this reason, in his

Novum Organum, Bacon advocates proceeding “regularly and gradually from one axiom to another, so that the most general are not reached till the last” (Simpson, n.d.). Therefore, through induction, “each step up the ladder of intellect is thoroughly tested by observation and experimentation before the next step is taken” and “each confirmed axiom becomes a foothold to a higher truth, with the most general axioms representing the last stage of the process” (Simpson, n.d.).

Abduction and the scientific method

It was not until Charles Sanders Peirce published

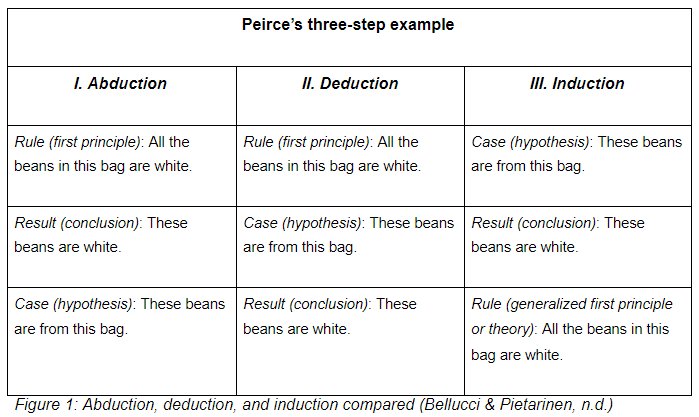

Deduction, Induction, and Hypothesis that the two ancient methods of reasoning were complemented by a more modern counterpart: abductive reasoning. Peirce’s approach was based on producing what he called a “case” (hypothesis) from a “result” (conclusion) and a “rule” (first principle).

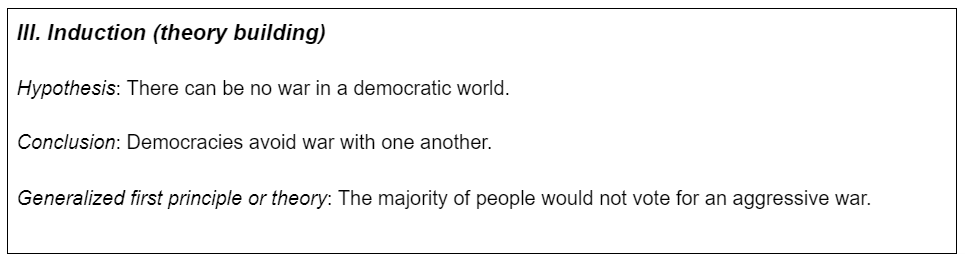

Figure 1 offers a comparative view of the three methods of reasoning as outlined in Peirce’s example of the bag of beans.

While abductive reasoning is the least logically secure of the three methods, it nevertheless facilitates making an inference about the best possible hypotheses to a research question given the limited information available to the researcher. The propositions produced through abduction can be tested subsequently through deduction, by which a valid “result” (conclusion) is inferred from the “case” (hypothesis) and the initial “rule” (first principle). Finally, induction can be used to generalize the products of the previous steps by extrapolating a universal “rule” (generalized first principle or theory) from a specific “result” (conclusion) and a “case” (hypothesis). In this way, the process of abduction-deduction-induction outlines the three basic steps of the scientific method: generating a hypothesis, testing the hypothesis, and generalizing the results or conclusions of the research to generate a theory.

Kant’s democratic peace theory

Between the time Descartes and Bacon investigated deductive and inductive reasoning and the time Peirce introduced his method of deduction, Immanuel Kant laid the groundwork for what would come to be known as the democratic peace theory. In

Perpetual Peace, Kant argues that it is reasonable for people to say that “there ought to be no war among us, for we want to make ourselves into a state; that is, we want to establish a supreme […] power which will reconcile our differences peacefully” (Ferraro, n.d.). In turn, it is also reasonable for the resulting state to say that “there ought to be no war between myself and other states” (Ferraro, n.d.). Therefore, if a group of people “can make itself a republic, which by its nature must be inclined to perpetual peace, this gives a fulcrum to the federation with other states so that they may adhere to it and thus secure freedom under the idea of the law of nations” (Ferraro, n.d.). As this federation of free republics grows, it will eventually expand to immerse the whole world in a league of democratic states that adheres to the universal law of nations, a perpetual peace.

Though Kant preceded Peirce and did not live to learn about abduction, the method can nevertheless be applied to the formation of Kant’s democratic peace theory. What follows is a step-by-step application of abductive, deductive, and inductive reasoning to the three steps of the scientific method—hypothesis generation, hypothesis testing, and theory generation—in the development of Kant’s democratic peace theory.

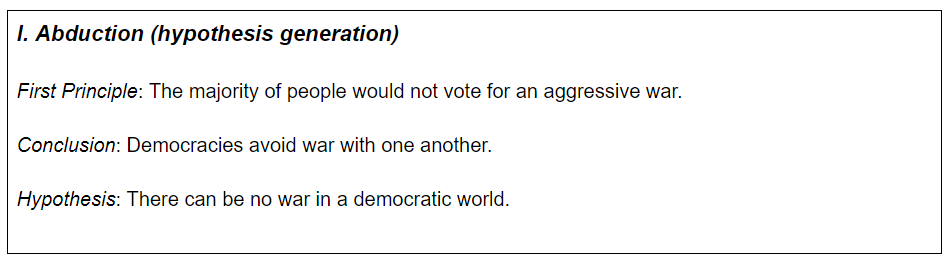

Based on the empirical observation that, even when left to their own devices, the majority of people do not behave aggressively with one another and tend to avoid violent conflict, Kant formulated the first principle that the majority of people would not vote for an aggressive war should they be given the choice. Furthermore, if the majority of people in a state would not vote for an aggressive war, then it can be concluded that two states governed by majority rule would avoid war with one another. Therefore, the first step of abductive reasoning leads to the hypothesis that there can be no war in a world composed entirely of democratic states.

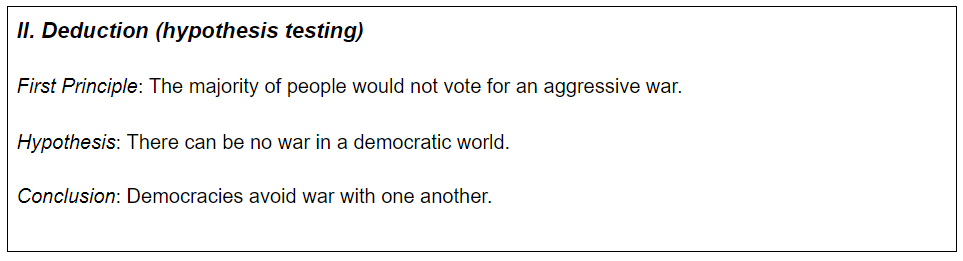

In order to test the validity of the hypothesis generated through abduction, it is necessary to see if a logical conclusion can be inferred from its relationship to the original first principle. Indeed, if the majority of people would not vote for an aggressive war, then there can be no war in a democratic world. Thus, the second step of deduction produces a conclusion that is not only logically valid with respect to the hypothesis and first principle but is also empirically observable. Though by contemporary standards there may not have been any truly democratic states in Kant’s time, the advent of universal suffrage in the 20th century has produced a considerable community of liberal democracies that do indeed maintain peaceful relations with one another.

Finally, based on the conclusion deduced from the initial hypothesis, the third and final step of the scientific method aims to generalize the fundamental first principle in order to generate a universally applicable theory. Therefore, if it is already accepted that there can be no war in a democratic world because democracies avoid war with one another, then it can be induced that this is true because the majority of people would not vote for an aggressive war. At this point, the three-step process returns to the first principle with which it began. However, while the first principle was initially nothing more than an axiom based on the empirical observation of individual human behavior, through the scientific method it was developed into a theory that presents a framework for understanding international relations.

From generation to application

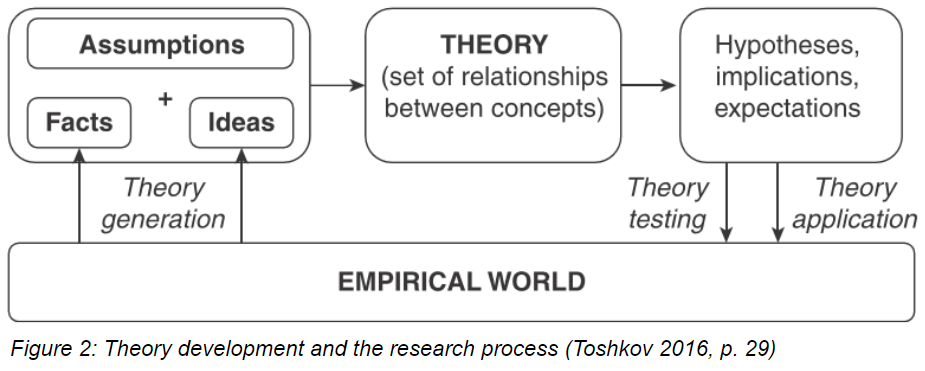

Following the first round of the scientific method, what started as a mere hypothesis about human nature is now proposed as a universal theory of global politics. However, before this novel theory can be applied to the empirical world, it should first undergo another round of scientific scrutiny to ensure that the underlying logic that supports it is indeed sound. This time, however, it is not necessary to begin with abductive reasoning as there is no need to generate new hypotheses. Instead, following the initial round of abduction-deduction-induction that led to the theory being generated, the researcher can return to deductive reasoning in order to test its validity on a macro level.

Figure 2 outlines this second round of examination.

At this point, it is important to begin by reviewing all the initial facts, assumptions, and ideas that form the basis of the theory. In the context of Kant’s democratic peace theory, the researcher must ask fundamental questions that might undermine the generalization of the first principle: “Are all societies equally peaceful?” or “Do sociological variables like wealth and culture affect individuals’ likelihood of aggression?”. Moreover, it is crucial to have clear definitions of all the concepts that comprise the theory: “What are the qualifying characteristics of a democratic state?” and “What exactly is meant by an aggressive war?”. By subjecting the theory to such tests, the researcher attempts to reveal any weaknesses that might invalidate the theoretical framework as a whole. Only after this second round of scrutiny can the researcher consider the implications and expectations of the theory before it is ready to be reapplied to the empirical world.

Conclusion

Assuming that Kant’s democratic peace theory passes the second round of scrutiny unscathed, can it finally be treated as a scientific law in the same way as Newton’s law of gravity, for example? Like laws, theories are epistemologically valuable for their descriptive and explanatory nature. They help researchers understand how things are by making comprehensible connections between abstract concepts and the natural world, and they also help explain why things are by mapping the causal relationships between different phenomena. However, unlike laws, they lack an absolute predictive quality. While the first principle that the majority of people would not vote for an aggressive war may hold true today and is most likely to hold true in the foreseeable future, it cannot be said with certainty that it would hold true under all circumstances. A widespread conspiracy, disinformation campaigns, fear tactics, and manipulation of the democratic process could all plausibly contribute to a violation of this first principle. So far, however, Kant’s theory and the first principles on which it rests have given advocates of democratic government reason to be optimistic.

References

- Bellucci, F., & Pietarinen, A.-V. (n.d.). Charles Sanders Peirce: Logic. In The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://www.iep.utm.edu/peir-log/#SSH2bi

- Ferraro, V. (n.d.). Immanuel Kant Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch. Mount Holyoke College. https://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/kant/kant1.htm

- Lancaster University. (2003). History of Philosophy in the 17th and 18th Centuries: Descartes’ “Principles of Philosophy”. https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/users/philosophy/courses/211/Descartes'%20Principles.htm

- Simpson, D. (n.d.). Francis Bacon (1561-1626). In The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://iep.utm.edu/bacon/#SH2k

- Toshkov, D. (2016).

Research Design in Political Science (1st ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

Apply first principles thinking yourself?

Would you like to apply first principles thinking yourself and have your problem-solving experience published in the First Principles Thinking Review? Then be sure to check out the submission guidelines and send us your rough idea or topic proposal. Our editorial team would be happy to work with you to turn that idea into an article.

Share this page

Disclaimer : The views, thoughts and opinions expressed in submissions published by FIPS reflect those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views held by FIPS, the FIPS team or the authors' employer.

Copyrights : You are more than welcome to share this article. If you want to use this material, for example when writing an article of your own, keep in mind that we use cc license BY-NC-SA. Learn more about the cc license here .

What's new?